Lensa AI and the Trap of Otherworldly Beauty

As technology advances, we continue to envision ourselves further and further outside of our own bodies. That's not necessarily a good thing.

BeautyStyle

Lensa AI is full of red flags. The app, which prompts users to upload photos of themselves then spits out 50+ AI-generated portraits for $3.99, has been decried by artists as predatory to real, human-made artwork. Then, there’s the conundrum of privacy: The “Face Data” users submit can be used by Lensa’s parent company, Prisma AI, to further train its AI’s network, according to ArtNews. And of course, there’s the ease with which Lensa AI is able to transform innocent photos of fully-clothed women or children into AI-generated nudes, heightening concerns around non-consensual porn and deepfakes.

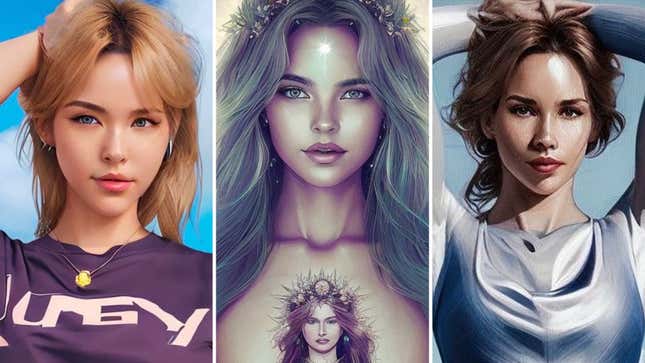

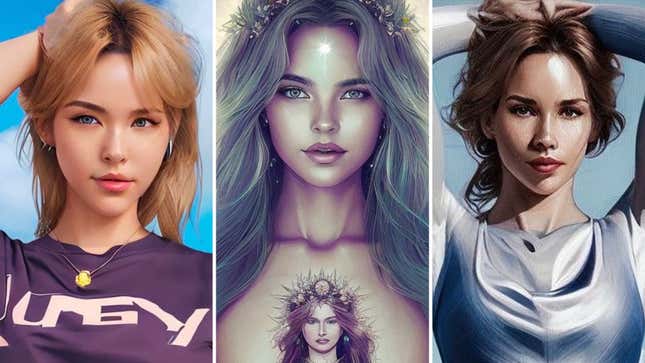

Nevertheless, Victorian women, erotic elves, French royals, and racially ambiguous intergalactic warriors took over social media feeds this week. According to TechCrunch, the app was downloaded 1.6 million times in November, with the U.S. generating 58% of the app’s sales. Women on TikTok posted collages of their ethereal portraits set to audio exclaiming, “how I love being a woman!” Celebrities including Chance the Rapper, MJ Rodriguez, and Sam Asghari also took part, uniting the rich and famous with the middle-class and ordinary in a quest for connection, validation, vanity, or some combination thereof.

Perhaps the inherent aesthetic value some people, especially women, seem to be getting from their Lensa AI portraits is as shallow as wanting to feel pretty. I get that. But what remains perplexing is consumers’ willingness to pay $3.99 for what are ultimately yassified and hyper-feminized representations of themselves that could easily be achieved with an Instagram filter at no cost. You’d be hard-pressed to get me to shell out a single dollar for an app, let alone one that I’d probably use once and delete.

When I posed this question to a few friends, one suggested that the pretension of celebrity is a reason we may be apt to override our better judgment for 50 portraits as glittering fairies—it’s as if someone’s taken the time to make fan art of us. She also wondered if it was “easier to buy into the delusion” that AI ran the numbers and decided, objectively, you were “GORGEOUS,” as opposed to applying a filter, which fashions you complicit in the beautification process. Another friend, Matt West, said his entire feed was a deluge of gay men posting AI thirst traps. “Everyone low key wants to be Rose from the Titanic,” he said.

The idea of magic avatars isn’t new, nor are the insidious implications of AI-generated representations of beauty. What’s different with this latest application of artificial intelligence is our accessibility to it. The vanity and promise of ethereal beauty is surely a fun one. But how might that in turn influence expectations around our faces, bodies, and the modification of both?

“Our current ideal of beauty, specifically in Western culture, specifically at this time in history, means being as divorced from your humanity as possible,” beauty culture critic Jessica DeFino told Jezebel. “These AI drawings have almost no humanity in them: They’re cartoon, digital renderings, created by artificial intelligence without a human hand involved in the making of it all. It just feels very depressingly on track for what our culture considers beautiful.”

@noelleleyva #greenscreen interesting

When DeFino says Lensa is “on track” with current beauty standards, she means that it follows other humanity-shedding trends like glass skin, jello skin, and vampire skin (which aspires to look “undead”). The same literal self-objectification, she said, can be seen within the Instagram face trend, in which consumers try to emulate Instagram and Facetune filters with cosmetics and surgery. AI-inspired beauty, or “meta face” as DeFino calls it, is the next natural step as we navigate between the physical world and the metaverse. Cartoonish in nature, youthful, and devoid of both texture and tone deviation, meta face (inspired by Mark Zuckerberg’s “waxy visage”) and Lensa AI together provide one of the first digital forays into otherworldly aesthetics: How beautiful you might look somewhere—really, anywhere—else without the constraints of gravity and your own humanity.

“It shows just how much our beauty culture conditioning overrides common sense without considering any of the downstream consequences,” DeFino said. “The human longing to be beautiful, to feel beautiful, to be surrounded by beauty, and to be part of beauty takes precedence over a lot of other human urges to the point that we will put ourselves in harm’s way to look or feel as beautiful as possible.” That harm can manifest physically—including unintended side-effects of injectables or cosmetic procedures—or mentally, with appearance-related anxiety, depression, dysmorphia, or worse.

Lensa AI’s iteration of beauty, of course, is a fantasy. But Vanessa Angélica Villarreal, a writer and poet who studies, among other things, the affective geographies of fantasy, argues that consumers derive value directly from that fantastical realism.

“When we think about fantasy, we think a lot about history, and this medievalized version of the world is very much steeped in Eurocentric whiteness,” Villarreal told Jezebel. “But fantasy is so much more expansive than that: Social media and the metaverse are expressions of fantasy. To me, fantasy is actually how we engage our collective imaginaries, and AI is this intelligent accumulation of data that creates a world that reflects our most basic impulses back to us.”

For starters, look at elves, who Villarreal says first appeared in literature in a Norse collection of mythology that predates the concept of race. There, elves represented pure beings of light and otherworldly beauty. As they evolved, especially in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings series, elves were conceptualized as “luminous, pure white beings…with the thinnest possible bodies.” Tolkien’s take on elves was published during World War II, making elves, Villarreal said, “the ultimate expression of Eurocentric beauty, and, by nature, whiteness”—which may at least partially explain why Lensa AI, in its production of images, frequently evokes the creatures.

Not only is the proliferation of these images adding to already-existing misogyny; they’re also explicitly racist. One Jewish woman said her nose was made “so much smaller.” Black women said their skin was lightened, mixed race women said their racial nuances were all but erased, and some Asian American women found themselves looking like femme-bots. Given that Lensa AI bills itself as taking photos “to the next level” to “perfect the facial imperfections,” erasing and minimizing the features of women of color means the AI deems them undesirable.

That’s all par for the course with AI, though. Villarreal noted that chatbots have repeatedly adopted neo-Nazi ideologies and the 19-year-old robot influencer Miquela’s racial ambiguity trends white. Academic scholars have demonstrated over and over again that AI is designed to produce overwhelmingly white imagery.

“Technology is affecting how we see ourselves and how we see others and how we want to see ourselves,” said DeFino. “If you look at the demographics of Silicon Valley, where a lot of this technology is coming out of, it is largely run by rich, older white men. And it is impossible to divorce their value systems from the products that are dispersed throughout society. Those biases are woven into a lot of our technology, specifically when it comes to gendered beauty ideals.” The world’s first digital supermodel, Shudu, for example, is a South Sudanese-presenting Black woman. She was conceptualized by a white man.

Of course, for some, Lensa AI has provided a sense of joy and relief, crafting images that affirm the identities of trans people experiencing gender dysmorphia. Just as in The Sims or in RPG video games, users get to live through avatars that represent and make real an idealized version of themselves, Villarreal said.

@christalluster #lensa #aipictures #trending #reactionvids @Lensa Photo Editing

As technology advances, we continue to envision ourselves further and further outside of our own bodies. All the while, DeFino said, the mainstream beauty industry has given us a sense of entitlement to features that are not ours, from injectables to contouring to fake eyelashes. Lensa AI has intensified that entitlement, suggesting that we’re entitled to a beauty that does not exist and a body that is not real. And as we float deeper into the possibilities of the metaverse, where everything is smooth and pretty and idealized, we float further from our humanity—the only true beauty we ever had.